The median nerve is one of the most important nerves in the arm, running from the neck down through the shoulder, forearm, wrist, and into the hand. When this nerve becomes compressed, irritated, or tight, it can create tingling, numbness, or weakness in the hand and forearm. One way people attempt to ease this discomfort is through nerve gliding or stretching.

The median nerve stretch is a safe and effective exercise when performed correctly, but doing it improperly can actually make symptoms worse. Learning how to do it with care is key for anyone managing nerve-related discomfort, whether caused by carpal tunnel syndrome, repetitive work activities, or poor posture.

Why Stretch the Median Nerve?

Stretching nerves may sound unusual because most people are used to stretching muscles. Yet nerves, much like muscles and tendons, move through tight pathways, weave around bones, and slip under muscles. Over time, repetitive motions, prolonged positions, or swelling can cause nerves to lose some of their normal mobility. Median nerve stretching helps restore normal gliding of the nerve, which can reduce irritation and improve comfort during daily activities.

Imagine a power cord running through a narrow tunnel. If the cord becomes stuck or bent, the electricity does not flow as smoothly. The same thing happens with nerves. A restricted nerve can send signals that feel like buzzing, tingling, or a burning sensation. Stretching allows that “cord” to slide more freely again.

Many everyday situations create stress on the median nerve. Hours of typing at a computer, gripping tools tightly, or even holding a smartphone with the wrist bent can all shorten and tighten tissues around the nerve. Conditions like carpal tunnel syndrome, thoracic outlet syndrome, or cervical disc issues make the nerve even more vulnerable. In these cases, stretching and gliding exercises become a way to release tension and restore natural function.

That said, stretching is not a cure-all. For some people, the issue may come from arthritis, diabetes, or structural changes in the wrist or spine. In those cases, nerve stretches play a supportive role but may not resolve the root problem. This is why knowing when and how to use them matters.

Preparing for a Safe Nerve Stretch

Jumping straight into a nerve stretch without preparation often leads to irritation. Nerves are highly sensitive tissues that prefer slow, controlled movement over aggressive pulling. A safe median nerve stretch always begins with relaxation, posture correction, and awareness of body signals.

First, check your posture. Sit or stand upright with your shoulders down and back. Let your chest open and your chin tuck slightly, as though balancing your head on top of your spine. This simple adjustment creates space around the nerves that exit your neck.

Second, do a short warm-up for your arms and wrists. Circle your wrists ten times in each direction, gently shake your hands, or squeeze a soft ball for a minute. These light actions bring blood flow to the muscles and prepare the nerve to move more comfortably.

Third, pay attention to your environment. Stretch in a place where you feel relaxed and not rushed. If your shoulders are hunched from stress or your body is tense from cold air, the stretch will be less effective. A warm, calm space helps you tune into your body’s signals.

Finally, set your expectations. The sensation should be mild, perhaps a gentle pull or light tingling, never sharp or painful. If your fingers go numb or your arm feels weak, stop immediately. Listening to your body is the most important safety step in nerve stretching.

How to Perform the Median Nerve Stretch

There are several safe ways to stretch or glide the median nerve, and each has its benefits. The most important factor is slow, careful execution rather than the intensity of the stretch. The safest approach is to move gradually, hold only mild tension, and breathe steadily throughout the exercise.

Step-by-Step Stretch (Basic Version)

- Starting Position

Stand upright or sit tall with both arms relaxed at your sides. Keep shoulders away from your ears. - Arm Extension

Slowly extend your right arm straight out to the side at shoulder height. Keep the elbow locked straight. - Wrist and Finger Position

Turn your palm up toward the ceiling, then extend your fingers and wrist backward as if signaling “stop.” You should feel a light pull in your forearm or palm. - Head Movement

For a deeper stretch, tilt your head gently away from the arm. If your right arm is extended, tilt your head toward your left shoulder. - Hold and Breathe

Hold for 10–15 seconds, focusing on slow, steady breaths. Release the tension by returning your arm to your side. - Repeat

Perform two or three repetitions per arm, alternating sides if both are affected.

Advanced Glide Variation

Once you are comfortable with the basic version, nerve gliding can help mobilize the nerve without holding a static position.

- Extend your arm and wrist as described above.

- Slowly bend your elbow, bringing your palm toward your shoulder, while tilting your head toward that same shoulder.

- Straighten the arm back out while tilting your head gently away.

- Repeat 5–10 times, moving in a smooth rhythm.

Nerve gliding focuses on motion rather than holding, making it useful for people with more sensitive symptoms.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Nerve stretches can feel deceptively simple, which is why they are easy to overdo. The most common mistake is treating nerves like muscles, pushing hard or holding too long, which aggravates symptoms rather than easing them.

Another mistake is ignoring posture. Slouching while stretching limits space in the shoulder and neck, creating more compression on the nerve. The result is frustration rather than relief.

People also tend to rush. Doing one quick stretch and expecting long-term results is unrealistic. Just like brushing teeth, nerve care works best with small, daily habits.

Breathing is another overlooked element. Holding your breath tenses muscles and stiffens the chest, which reduces relaxation. Exhaling slowly as you stretch tells your nervous system it is safe to release tension.

Finally, ignoring warning signs is risky. Persistent numbness, spreading pain, or dropping objects due to weakness are signs to stop and seek professional care. Red flags should never be pushed through, no matter how committed you are to stretching.

When to Seek Professional Guidance

Not everyone should begin nerve stretches without guidance. If your symptoms are severe, persistent, or disrupting daily life, it is time to consult a physical therapist, occupational therapist, or physician.

Carpal tunnel syndrome, for example, often requires wrist splints, ergonomic changes, or medical evaluation. Cervical disc herniations may irritate the median nerve near the spine, making wrist-focused stretches less effective. A professional can identify whether your issue comes from the wrist, elbow, shoulder, or neck, and design a treatment plan that combines stretches with strengthening, ergonomic advice, and sometimes medical interventions.

In a therapy setting, median nerve stretches are often paired with exercises for grip strength, shoulder stability, and posture. This combination reduces the chance of recurrence. Professional guidance also helps you progress safely, increasing intensity only when your body is ready.

Integrating the Stretch Into Daily Life

Consistency matters more than intensity when it comes to nerve health. The best way to benefit from median nerve stretches is to weave them into your daily routine as short, mindful breaks.

If you work at a desk, set a reminder every two hours to stand, stretch your arms, and perform a few glides. Those in trades like carpentry or electrical work can use the stretch as a recovery exercise at lunch or after long periods of gripping tools.

Pairing the stretch with existing habits makes it easier to remember. Doing it after brushing your teeth, while waiting for your coffee to brew, or before climbing into bed builds automatic consistency.

Lifestyle adjustments also make a difference. Adjust your workstation so your wrists remain neutral while typing. Take breaks to stand and roll your shoulders. Use supportive pillows if you sleep with your wrists bent. These small changes support the benefits of stretching.

Supportive Practices

- Strengthening exercises: Build wrist and forearm strength with light resistance bands. Strong muscles support freer nerve movement.

- Postural awareness: Regularly check your sitting and standing posture. Poor alignment at the neck and shoulders creates unnecessary compression.

- Mindful breaks: Every 30–45 minutes, pause and move your hands, wrists, and shoulders. Preventing stiffness reduces nerve irritation.

Table: Stretching vs Gliding for Median Nerve

| Aspect | Static Stretch | Nerve Glide |

| Technique | Hold position for 10–15 seconds | Gentle repeated back-and-forth motion |

| Sensation | Light pull or tingling | Smooth sliding with less intensity |

| Best for | Mild stiffness or tightness | Irritation, sensitivity, or rehab |

| Frequency | 2–3 times per session, daily | 5–10 reps, 1–2 times per day |

| Risk | Higher if overdone | Lower when performed slowly |

Both methods have value, but gliding is often better for sensitive nerves, while static stretching can help when stiffness is the main issue.

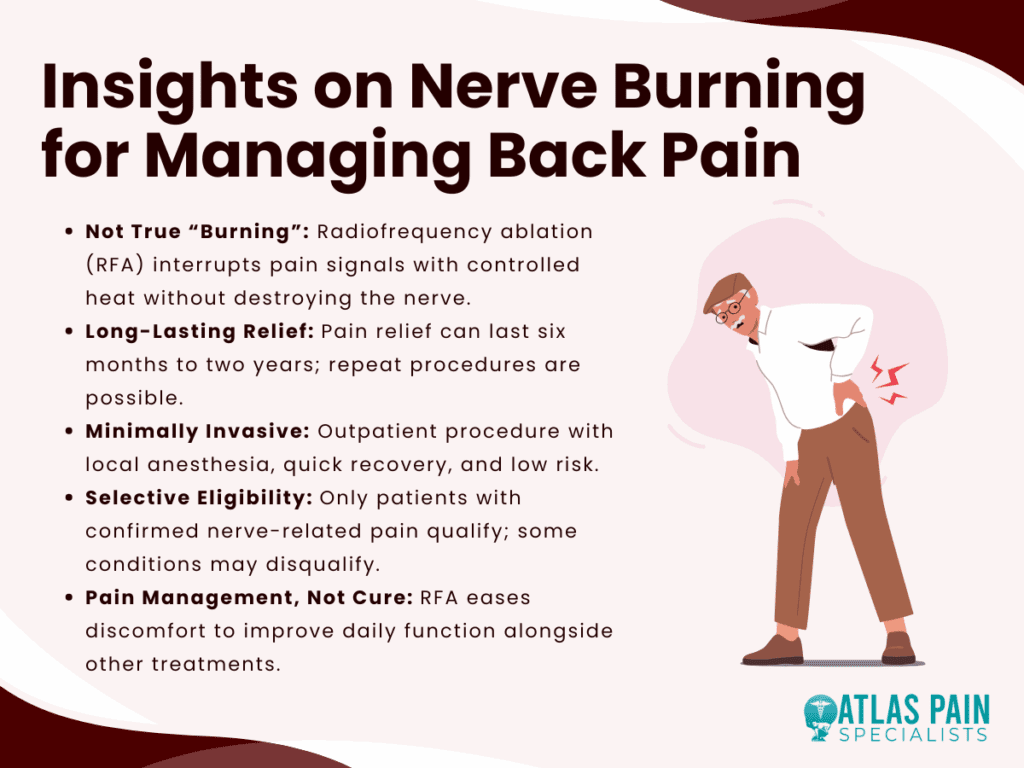

Five Things You Didn’t Know About Nerve Burning for Back Pain

Living with back pain often leads people to explore treatments they may have never considered before, and nerve burning is one of those approaches that can sound surprising at first. By learning more about how it works, how long it lasts, who it helps, and what the risks are, you can approach the decision with clarity rather than confusion.

The more you understand about nerve burning, the better prepared you are to talk with your doctor and decide if it fits into your plan for managing back pain. It may not be the right path for everyone, but for those who find relief, it can open the door to moving more freely and enjoying daily life with less discomfort.

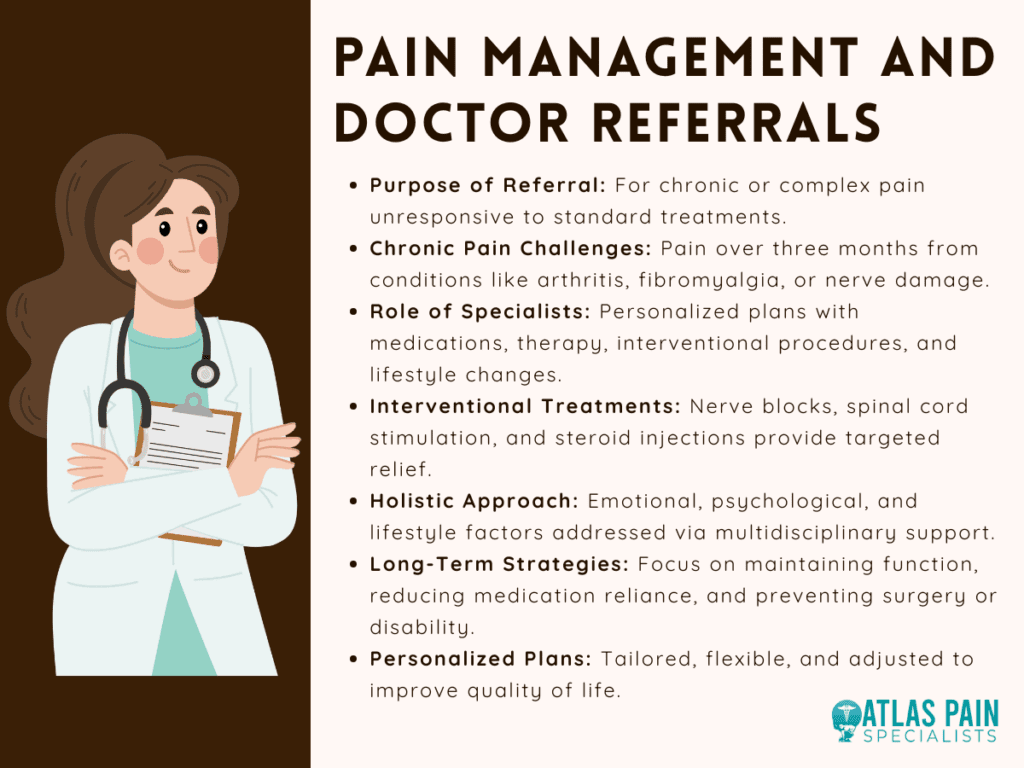

When patients hear that their doctor is referring them to pain management, it often raises questions and even some concern. Many people are unsure what a pain management specialist does or why such a referral might be necessary.

In reality, this step usually means that your physician wants you to receive more focused care for persistent or complex pain issues. Pain management clinics are designed to address conditions that may not improve with standard treatment and offer advanced therapies.

Pain is not only a physical experience but also one that affects emotional health, work performance, and overall quality of life. Pain management specialists use targeted methods that range from interventional procedures to tailored rehabilitation programs. Why is my doctor sending me to pain management? Let's find out.

Chronic Pain That’s Not Responding to Standard Treatments

One of the most common reasons your doctor might send you to pain management is if your pain has become chronic and is no longer responding to standard treatments. Chronic pain is defined as pain that lasts for more than three months and persists even after the injury or illness has healed.

It can result from various conditions, including arthritis, fibromyalgia, and nerve damage.

Standard Treatments Often Aren’t Enough

When a person first develops pain, common treatments like rest, over-the-counter pain relievers (acetaminophen, ibuprofen), or physical therapy may help. However, chronic pain can often be stubborn, and these initial treatments may lose their effectiveness over time.

For instance, what worked for you in the beginning may not work as your pain becomes more entrenched.

The Role of Pain Management Specialists

Pain management specialists are trained to approach pain from a multi-faceted perspective. When chronic pain persists despite conventional treatments, a pain management specialist will assess your situation carefully and design a comprehensive treatment plan.

This may include a combination of therapies both medical and non-medical that aim to alleviate the pain and restore function. Since each individual experiences pain differently, your pain management specialist will develop a personalized When patients hear that their doctor is referring them to pain management, it often raises questions and even some concern. Many people are unsure what a pain management specialist does or why such a referral might be necessary. In reality, this step usually means that your physician wants you to receive more focused care for persistent or complex pain issues. Pain management clinics are designed to address conditions that may not improve with standard treatment, offering advanced therapies and a multidisciplinary approach.

Pain is not only a physical experience but also one that affects emotional health, work performance, and overall quality of life. A primary care doctor may treat initial symptoms, but chronic or severe pain requires specialized strategies that go beyond basic prescriptions. Pain management specialists use targeted methods that range from interventional procedures to tailored rehabilitation programs. Being referred to one of these clinics is not a dismissal from your doctor but rather an opportunity to receive comprehensive care that prioritizes your long-term well-being.plan for your unique needs.

Managing Complex Pain Conditions

Pain is not always straightforward. Conditions such as fibromyalgia, neuropathy, and complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) involve complex pain mechanisms that may not be well understood and can be difficult to treat with traditional methods.

Fibromyalgia and Neuropathy

Fibromyalgia, a condition that causes widespread pain and tenderness throughout the body, often comes with other symptoms such as fatigue, sleep disturbances, and difficulty concentrating.

The pain associated with fibromyalgia is often diffuse and can change in intensity over time, making it difficult to treat. Similarly, neuropathy (nerve damage) causes sensations like tingling, burning, or numbness, often in the hands and feet.

These conditions can be incredibly disruptive and require specialized care.

The Complexity of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS)

Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is a condition that typically affects an arm or leg after an injury. The pain is often severe and out of proportion to the original injury and can include swelling, changes in skin color, and sensitivity to touch.

Managing CRPS requires advanced pain management techniques to address the abnormal nerve responses and inflammatory processes involved.

Pain Management for Complex Conditions

A pain management specialist is well-equipped to treat these complex conditions with a variety of methods, such as nerve blocks, spinal cord stimulation, and medications that target the nervous system.

They may also incorporate alternative treatments like acupuncture or biofeedback, which help patients manage pain without relying solely on medication. The goal is not just to relieve pain, but to also improve your overall quality of life and functionality.

Interventional Procedures for Targeted Relief

For some people, pain medications and physical therapy alone are insufficient. This is where interventional pain management comes in. Interventional pain management refers to minimally invasive procedures designed to directly target the source of pain, offering more focused and effective relief than oral medications.

Common Interventional Techniques

Some common interventional procedures include:

- Epidural Steroid Injections: These are used to reduce inflammation around the spinal cord and nerve roots. They’re often recommended for conditions like sciatica, herniated discs, or spinal stenosis. The goal is to provide temporary relief, allowing other treatments (such as physical therapy) to be more effective.

- Nerve Blocks: Involves injecting an anesthetic near a nerve to block pain signals. Nerve blocks are commonly used for conditions like migraines, joint pain, or specific nerve-related pain.

- Spinal Cord Stimulation: This technique involves implanting a small device near the spinal cord to deliver electrical impulses, which can block pain signals and help alleviate chronic pain.

Minimally Invasive and Effective

These interventional techniques are often performed under local anesthesia, and recovery times are relatively short compared to surgery. They allow pain management specialists to treat localized pain without requiring large incisions or long recovery periods.

The goal of these procedures is not necessarily to "cure" the pain but to give you significant, lasting relief that improves your ability to function in your daily life.

A Holistic, Multi-Disciplinary Approach

Pain management is not just about using medication to numb symptoms. In fact, a holistic, multi-disciplinary approach is often one of the most effective ways to manage chronic pain.

This approach recognizes that pain affects the whole person not just the physical body and addresses the emotional, mental, and lifestyle components as well.

The Role of a Multidisciplinary Team

Your pain management specialist will often collaborate with other healthcare professionals, including physical therapists, occupational therapists, psychologists, and sometimes even nutritionists.

For example, physical therapy can help you strengthen muscles and improve mobility, while occupational therapy can teach you techniques to perform daily activities with less discomfort.

Psychological Support

Pain can take a heavy toll on mental and emotional health. Chronic pain often leads to depression, anxiety, and frustration.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is a form of therapy that helps individuals develop coping strategies and change negative thought patterns associated with pain.

Pain management specialists will often recommend CBT or other psychological therapies as part of a comprehensive treatment plan to help you manage the emotional and psychological aspects of chronic pain.

Long-Term Pain Management Strategies

Chronic pain isn’t something that can always be eliminated entirely, especially if it’s linked to a long-term condition like arthritis, fibromyalgia, or nerve damage. For this reason, pain management specialists often focus on developing long-term strategies that aim to reduce pain flare-ups and improve your overall quality of life.

Maintaining Function and Mobility

The ultimate goal of pain management is not just to eliminate pain but to ensure that you can continue functioning and enjoying life despite the pain. A pain management specialist will work with you to create a sustainable plan for reducing pain and improving your mobility. This plan might include a combination of exercises, therapy, lifestyle changes, and medication that will allow you to stay active and independent.

Avoiding Dependency on Medication

Another key goal of long-term pain management is to minimize the risk of dependency on pain medications. Many people with chronic pain rely on medications like opioids to manage their symptoms.

However, these medications can be addictive and have side effects. Pain management specialists focus on using the smallest effective dose of medication and may explore other non-medication options to help you manage pain without over-relying on drugs.

Medication Management and Monitoring

If you’re currently taking pain medications, particularly opioids or other potent painkillers, the management and monitoring of these medications becomes an important part of your care. Pain management specialists are skilled in managing medication use to ensure it remains safe and effective over time.

The Importance of Monitoring Medication Use

Pain management specialists are trained to assess the risks of long-term medication use, particularly when it comes to opioid medications, which carry a risk of dependence and other side effects.

They will closely monitor your progress and adjust your medications as necessary to help you maintain an effective pain management regimen. If opioids are part of your treatment plan, they will help you manage your use in a way that minimizes the risk of addiction or misuse.

Exploring Non-Medication Alternatives

In addition to medication, pain management specialists will often recommend non-pharmaceutical treatments, such as acupuncture, massage therapy, or chiropractic care. These alternative treatments can be effective in reducing pain, and they offer valuable options for people who are looking to avoid or reduce their reliance on medications.

Preventing Surgery and Disability

Pain management specialists aim to help you avoid surgery whenever possible, especially if the pain can be controlled through less invasive means. In some cases, untreated chronic pain can lead to disability or the need for surgery, but pain management specialists work to reduce or prevent these outcomes by offering alternative treatments.

Avoiding Surgical Interventions

In some cases, surgery may be the most effective solution, such as with certain types of spinal issues or joint problems. However, a pain management specialist will help you explore all options first, offering treatments that might reduce pain enough to avoid surgery altogether.

Minimally invasive procedures, physical therapy, or medications may be able to manage your pain without the need for invasive surgery.

Maintaining a High Quality of Life

By providing targeted pain relief and treatment strategies, pain management specialists can help prevent disability, allowing you to continue living independently and participating in daily activities. Their goal is to help you maintain a high quality of life, no matter the challenges your pain condition presents.

Personalized Treatment Plans

Each individual experiences pain differently, and effective pain management relies on a highly personalized approach. When you see a pain management specialist, they will work closely with you to create a treatment plan tailored to your specific condition, needs, and lifestyle.

Individualized Care

Your pain management plan will take into account factors like the type and location of your pain, your personal medical history, and your goals for treatment. Whether it involves medications, physical therapy, psychological therapy, or interventional procedures, your treatment plan will be designed to help you achieve the best possible outcome.

Flexibility and Adjustments

Pain management is a dynamic process, and your specialist will regularly reassess your progress and make adjustments to your treatment plan as needed. As your condition evolves or as new treatments become available, your specialist will ensure that your plan stays relevant and effective.

What to Expect from a Pain Management Doctor

When a doctor refers a patient to pain management, it signifies an important step toward specialized care rather than an inability to help. Pain management clinics provide access to advanced treatments, a range of therapeutic options, and expertise.

These clinics focus on long-term solutions, helping patients reduce discomfort, regain mobility, and improve quality of life. A pain management doctor dedicates time to evaluating the full scope of a patient’s condition, considering medical history, lifestyle, and previous attempts at relief.

Patients can expect a detailed consultation in which the doctor listens carefully to their concerns and explains the different avenues of care. A pain management doctor also provides access to a wide range of therapies that can be combined to form a personalized plan.

Back pain is one of the most common complaints in the United States, affecting millions of adults each year. It disrupts sleep, limits work, and changes how people go about everyday life. While physical therapy, medications, and exercise often help, many people find that these measures only go so far. For those who live with persistent discomfort, a treatment called radiofrequency ablation—often nicknamed “nerve burning” sometimes enters the conversation. The name alone can be enough to spark anxiety, yet the reality of the procedure is different than most imagine. Nerve burning is not a destructive act but a carefully planned therapy designed to reduce pain signals and improve daily function.

Below are five things most people do not know about this treatment, explained in detail to show where it fits into modern back pain care.

1. It’s Not Actually “Burning” in the Way You Think

The name “nerve burning” paints a dramatic picture, but the truth is far more refined. The medical term for the procedure is radiofrequency ablation, or RFA. During the treatment, a doctor inserts a thin probe through the skin to reach the nerve suspected of carrying pain signals. Imaging technology like fluoroscopy is used to ensure accurate placement. Once in position, radio waves generate heat at the tip of the probe, interrupting the nerve’s ability to transmit pain.

What happens is not the fiery destruction of tissue but a controlled interference in communication between the nerve and the brain. This interference reduces the sensation of pain without eliminating the nerve completely. Over time, the nerve often regenerates, which is why the procedure can be repeated when needed.

Precision Targeting of Nerves

A fascinating detail is the precision behind the therapy. Doctors use test stimulations before applying radiofrequency, ensuring the correct nerves are targeted. This method spares surrounding muscles and tissue from unnecessary damage. Compared with surgery, which physically alters structure-

s of the spine, this targeted approach is gentler, reversible, and far less risky.

A Misunderstood Name

The term “burning” has stuck partly because of the heat involved, but it has led to misunderstandings. Many patients initially fear the idea of scorched nerves, only to be surprised when their physician explains the subtlety of the treatment. Understanding this distinction helps patients approach the procedure with more confidence and less apprehension.

2. Relief Can Last Longer Than You’d Expect

Some people assume nerve burning only offers a short-term reprieve, similar to an injection that wears off quickly. In reality, the results often last far longer. On average, pain relief ranges from six months to two years. This wide window reflects differences in health, age, the underlying condition, and lifestyle habits.

Radiofrequency ablation acts as a middle ground between quick fixes like steroid shots and major steps like surgery. It gives patients time to regain control of their lives without committing to the permanent changes and risks of invasive operations.

Why Relief Varies

The longevity of relief depends on how quickly the nerve regenerates. In some individuals, regrowth may occur sooner, while in others, the benefits last years. Factors such as arthritis severity, physical activity, and weight can also play roles. For example, someone with advanced degenerative disc disease may find that relief lasts closer to the shorter end of the spectrum, while someone with localized facet joint pain may enjoy longer results.

The Value of Repeat Procedures

Another underappreciated advantage is the ability to repeat the procedure. Once a patient responds well the first time, doctors are usually confident about offering another session when pain returns. This creates a cycle of relief that can be maintained over the years, reducing reliance on heavy medications or more invasive treatments.

3. It’s Minimally Invasive with a Quick Recovery

For people already tired of constant pain, the last thing they want is a long hospital stay or a difficult recovery. Radiofrequency ablation avoids this problem entirely. The procedure is performed in an outpatient setting and usually takes less than an hour. Patients receive local anesthesia and sometimes mild sedation but rarely require general anesthesia.

Recovery is quick, with most people returning to their usual activities within a few days. Some even go back to work the next day, depending on their comfort level. This ease surprises many who expected weeks of downtime.

Comparing Recovery with Surgery

When compared with spinal surgery, the difference is stark. Back operations often require weeks or months of rehabilitation, with risks such as infection, scarring, or long-term stiffness. By contrast, RFA leaves only a small puncture at the site of needle insertion. Discomfort afterward is usually mild soreness, which resolves quickly.

Risks and Safety Considerations

Every medical procedure carries risks, but RFA’s are relatively low. Infection and bleeding are rare, and serious complications like permanent nerve damage are uncommon. Most patients find the risks acceptable given the potential rewards, especially when compared with the side effects of long-term pain medications.

4. Not Everyone Qualifies for the Procedure

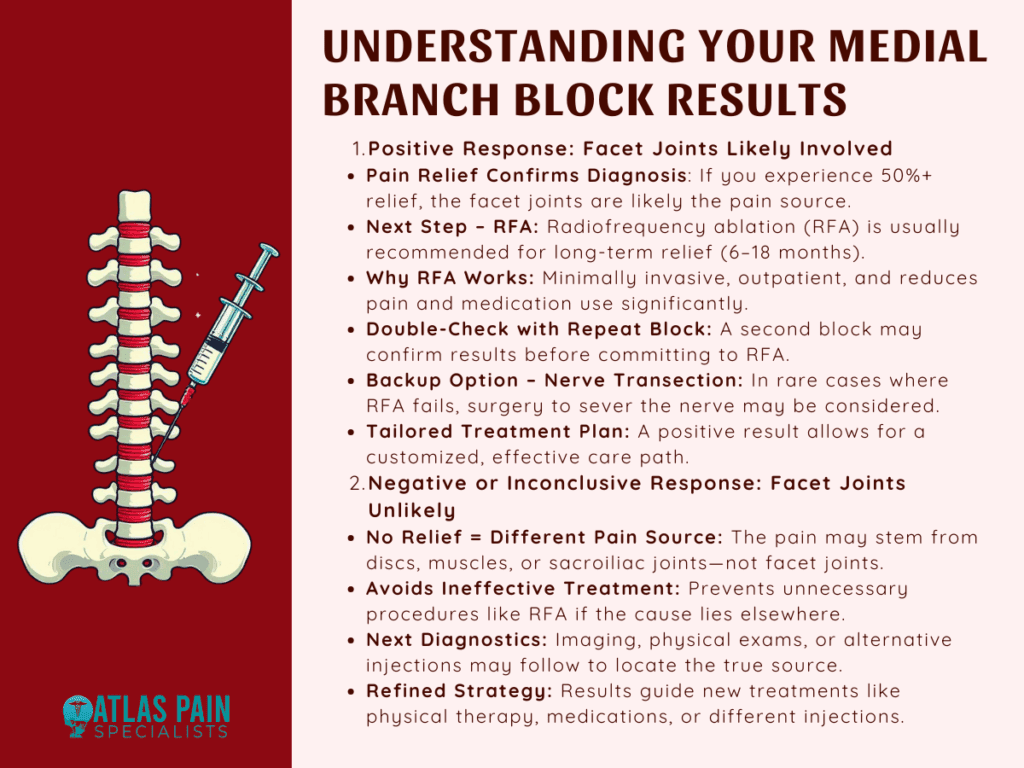

Despite its benefits, nerve burning is not offered to every patient with back pain. Physicians must first confirm that the pain originates from the nerves RFA is designed to target. To do this, they use a test called a diagnostic nerve block. A small amount of anesthetic is injected near the suspected nerve. If pain decreases significantly for the duration of the anesthetic’s effect, it suggests that RFA would be helpful.

This step ensures that only patients with nerve-related pain undergo the procedure, improving success rates and preventing unnecessary interventions.

Who May Not Qualify

Certain groups may not be good candidates. People with bleeding disorders or active infections are usually advised against the procedure. Those with pacemakers or other implantable devices may need special precautions. Additionally, patients whose pain stems mainly from muscle strain, herniated discs, or systemic illness may not benefit.

The Importance of Specialist Evaluation

Because back pain can have many sources, a thorough evaluation is vital. Pain specialists, interventional radiologists, or anesthesiologists trained in this therapy are best equipped to determine eligibility. Their expertise helps ensure that the right patients receive the right treatment.

5. It Doesn’t Cure Back Pain but Manages It Effectively

One of the biggest misconceptions about nerve burning is that it offers a permanent cure. While the relief can be dramatic, it does not stop the underlying condition that caused the pain in the first place. Arthritis, disc degeneration, and spinal stenosis remain even after nerves are quieted.

What RFA does is buy patients the freedom to live more comfortably while addressing their condition through other means. This makes it a powerful tool in a comprehensive plan rather than a standalone solution.

Combining RFA with Other Therapies

For many patients, the procedure creates an opportunity to re-engage in physical therapy or exercise programs that were impossible when pain was overwhelming. Improved movement allows for muscle strengthening, weight management, and healthier posture. These changes support long-term back health and can extend the benefits of the procedure.

Quality of Life Matters

Even when pain eventually returns, many people report that the months or years of relief transformed their lives. Being able to sleep without constant discomfort, walk without frequent stops, or work with fewer limitations are meaningful improvements that restore independence and well-being. In this sense, the measure of success is not a cure but a life lived more fully.

Comparing Nerve Burning to Other Back Pain Treatments

When looking at the landscape of back pain treatment, it becomes clear where radiofrequency ablation fits. It is more effective and longer-lasting than steroid injections, less invasive than surgery, and more immediate than physical therapy.

| Treatment | Invasiveness | Recovery Time | Duration of Relief | Ideal Use |

| Radiofrequency Ablation | Minimally invasive | A few days | 6 months to 2 years | Chronic nerve-related pain |

| Steroid Injections | Minimally invasive | 1–2 days | Weeks to months | Pain linked to inflammation |

| Physical Therapy | Non-invasive | Ongoing | Long-term with consistency | Mobility and strength building |

| Surgery | Highly invasive | Weeks to months | Potentially permanent but higher risks | Severe structural conditions |

| Medications | Non-invasive | None | Hours to days | Temporary symptom relief |

The table highlights how nerve burning balances effectiveness with safety. It does not replace other therapies but holds a distinct place as a middle-ground option for patients who need more than conservative care but want to avoid the risks of surgery.

Conclusion

Chronic back pain affects far more than the spine; it reshapes daily routines, limits independence, and erodes quality of life. Radiofrequency ablation, often misunderstood as a destructive treatment, offers a safe and precise way to reduce pain without major surgery. By quieting pain signals, it gives patients the breathing room to rebuild strength, reclaim mobility, and enjoy meaningful relief that lasts months or even years.

Although not everyone qualifies and it is not a cure, nerve burning stands as an important option within the spectrum of back pain management. Understanding its true nature helps patients and families make informed choices, moving from fear of the term “burning” to appreciation of its role in improving lives.

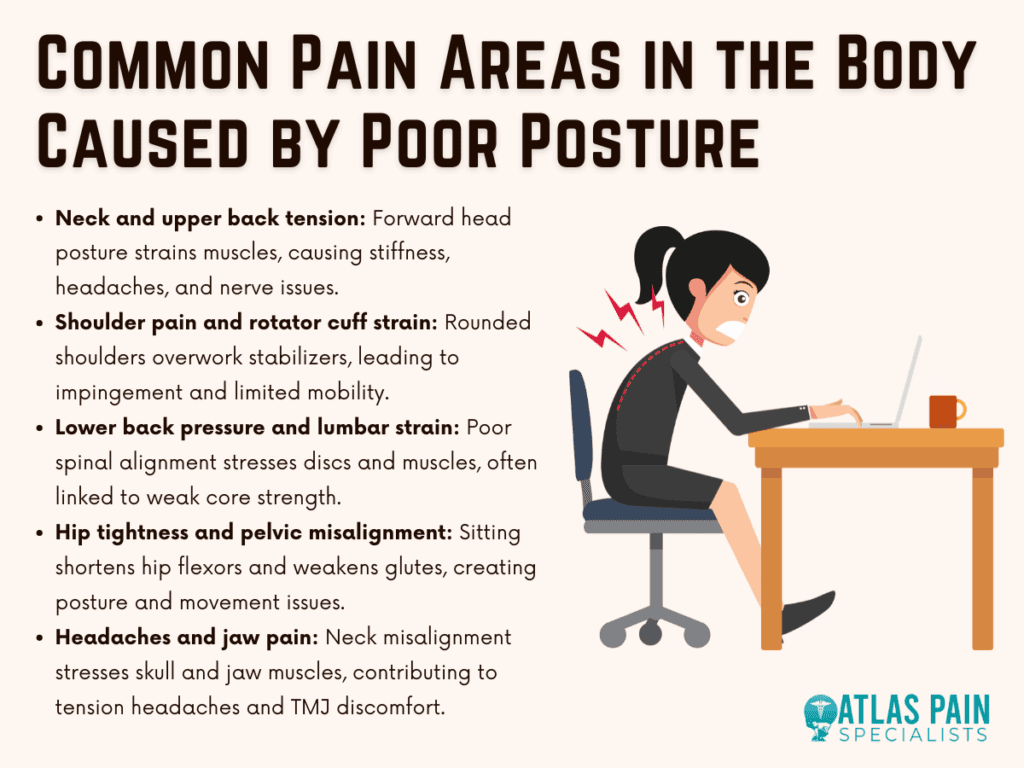

Poor posture is more than a visual habit, it’s a physical stressor that can quietly strain muscles, compress joints, and trigger long-term discomfort. Many people only realize the extent of the damage once pain becomes a daily issue. From your neck to your lower back, poor posture pain areas can affect multiple regions of the body, often overlapping and creating a chain reaction of tension.

Physical therapists often see this cascade effect in patients, where one misalignment in the spine or shoulders leads to discomfort in seemingly unrelated places. Recognizing these areas early is key to breaking the cycle before it becomes a chronic problem.

Neck and Upper Back Tension

Slouching or craning your head forward while working at a desk or looking down at a phone puts significant strain on the neck muscles. This “forward head posture” shifts the head’s weight from its natural alignment, making the neck muscles work overtime. Over time, the trapezius, levator scapulae, and cervical extensors can become tight and sore. The upper back often joins the complaint list because muscles like the rhomboids and upper trapezius have to compensate for poor head positioning.

The neck and upper back are often the first to feel the consequences of poor posture because they work constantly to support your head’s weight. Patients frequently report stiffness, headaches, and even tingling in the arms due to nerve compression. Physical therapists often recommend ergonomic desk setups, where the monitor is at eye level and the shoulders remain relaxed. Incorporating chin tucks, gentle neck stretches, and scapular retraction exercises into your daily routine can help re-balance muscle activity and restore proper alignment. Massage therapy or myofascial release can also be beneficial in breaking up chronic tightness in this region.

Many people underestimate the impact of posture on their circulation and energy levels, yet slouching or leaning forward for long stretches restricts the flow of blood and oxygen throughout the body. Over time, this can lead to feelings of fatigue, heaviness in the limbs, and even headaches caused by reduced oxygen delivery to the brain. Correcting posture often brings about a noticeable improvement in vitality because upright alignment allows the heart and lungs to function without unnecessary strain.

Shoulder Pain and Rotator Cuff Strain

Rounded shoulders are a classic sign of slouching, where the chest caves in and the upper spine curves forward. This posture shortens the pectoral muscles and overstretches the upper back muscles, disrupting the balance of the shoulder joint. Over time, the rotator cuff, the group of muscles stabilizing the shoulder, can become overworked and prone to injury. Poor shoulder positioning can lead to both muscle fatigue and joint instability, increasing your risk of rotator cuff problems.

Some people even develop impingement syndrome, where the tendons become irritated or pinched during movement. This makes overhead tasks like lifting groceries, reaching for a shelf, or even sleeping on your side uncomfortable. From a therapy perspective, strengthening the scapular stabilizers, such as the serratus anterior and lower trapezius, is vital. Stretching the pectoralis major and minor also helps open up the chest and improve shoulder mechanics.

Using resistance bands for external rotation exercises can strengthen the rotator cuff and reduce the strain caused by poor posture. When posture issues persist for years, structural changes can occur in the shoulder joint. This includes thickening of soft tissue structures or the development of bone spurs, which can further limit range of motion. These changes make early intervention even more important, as restoring muscle balance before irreversible joint damage occurs can prevent costly and invasive treatments later on.

Beyond physical pain, poor posture frequently contributes to psychological stress. Research suggests that posture can influence mood and self-perception, with slumped shoulders and a forward head position linked to feelings of low confidence and increased anxiety. On the other hand, standing or sitting tall with an open chest often promotes a sense of alertness and control, making posture correction a valuable tool for both physical and mental well-being.

Lower Back Pressure and Lumbar Strain

The lower back bears a heavy load when posture falters. Sitting with a rounded lower spine or standing with a swayback position shifts the natural curvature of the lumbar region, placing extra stress on spinal discs and surrounding muscles. This can lead to chronic tightness, disc degeneration, or even sciatic nerve irritation if the imbalance persists. When your lumbar spine loses its natural curve, muscles and joints are forced to absorb forces they weren’t designed to handle.

In the clinic, physical therapists often find that people with poor lumbar posture also have weak core muscles, making it harder to maintain stability. Core strengthening is one of the most effective interventions for lower back pain related to posture. This includes targeted exercises like pelvic tilts, dead bugs, and bridges. Using lumbar support cushions when sitting for long periods can help maintain spinal alignment. For those who stand most of the day, slightly elevating one foot on a low step or footrest can reduce pressure on the lumbar spine.

Poor posture also has significant implications for digestion. When the upper body collapses forward, it compresses the abdominal organs, limiting the stomach’s ability to process food efficiently. This can contribute to acid reflux, bloating, and slower metabolism, creating a cycle of discomfort that many people attribute to diet rather than posture. Developing a habit of maintaining a straight back and relaxed shoulders during and after meals can ease digestive strain considerably.

Hip Tightness and Pelvic Misalignment

Many people are surprised to learn that their hips can be a major site of pain from poor posture. Sitting for extended hours causes the hip flexors, particularly the iliopsoas, to shorten. This tightness can tilt the pelvis forward, a condition called anterior pelvic tilt, which adds stress to the lower back and even the knees. On the flip side, weak gluteal muscles from prolonged inactivity can make it difficult to stabilize the pelvis during walking or standing.

Tight hip flexors and weak glutes often go hand-in-hand, creating a cycle of discomfort that affects posture and movement efficiency. Patients often notice this when they struggle to fully extend their hips during walking, leading to a shorter stride and more lower back strain. Corrective strategies focus on lengthening tight muscles and strengthening underused ones. Hip flexor stretches, lunges, and bridges can restore mobility and stability. Incorporating dynamic movements like leg swings before workouts and glute activation drills before sitting for long periods can help maintain better pelvic alignment.

Long-term hip tightness can also affect the knees and ankles, as the body compensates for restricted movement in one area by overloading another. For example, if your hips cannot extend fully, your knees may absorb more shock during walking or running, leading to joint pain. Addressing hip mobility is therefore not just about comfort, it is a strategy for protecting the entire lower body from cascading posture-related injuries.

Headaches and Jaw Pain from Postural Stress

Poor posture doesn’t just affect the spine, it can extend to the skull and jaw. Forward head posture can tighten the sub occipital muscles at the base of the skull, which are linked to tension headaches. Additionally, misalignment in the neck can alter the position of the jaw joint (TMJ), leading to pain, clicking, or difficulty chewing. Postural misalignment in the neck can contribute to headaches and jaw discomfort by altering how muscles and joints function.

These symptoms often get worse with stress, as people tend to clench their jaw or grind their teeth, compounding the strain. Therapists addressing these issues often combine neck alignment exercises with relaxation techniques to reduce jaw clenching. Gentle stretching of the neck and facial muscles, along with awareness of resting jaw position, can relieve strain. In some cases, collaboration with a dentist or TMJ specialist ensures a comprehensive approach to care.

Many people don’t realize that poor posture contributes to heightened psychological stress. This is often compounded by slumping or hunching, which signals the body into a “fight-or-flight” response, further straining mental health. Even something as simple as sitting or standing with shoulders back and a straight spine can help reduce feelings of anxiety and increase your sense of control.

Preventing and Reversing Poor Posture Pain Areas

Poor posture can lead to a variety of aches and pains, but with consistent effort and small lifestyle changes, it’s possible to prevent and reverse the discomfort caused by misalignment. Addressing posture issues early can minimize long-term effects, and strengthening key muscle groups plays a major role in maintaining better posture. Below, we’ll explore strategies for both preventing and reversing posture-related pain.

Prevention Through Early Habits

Prevention is always easier than rehabilitation, and most posture-related pain can be minimized by adopting better habits early. A physical therapy approach typically involves three key steps: assessment, correction, and strengthening.

First, therapists evaluate movement patterns and muscle imbalances. Next, they introduce adjustments like ergonomic seating, proper footwear, or standing breaks. Finally, they implement strengthening programs targeting the core, upper back, and glutes.

Small Changes for Long-Term Improvement

Addressing poor posture is about consistent small changes rather than one dramatic fix. This might mean setting reminders to stand up every 30 minutes, practicing desk-friendly stretches, or swapping out your pillow for one that supports spinal alignment.

While some postural corrections take weeks to feel noticeable, maintaining an active lifestyle and monitoring how your body feels during daily tasks can prevent these pain areas from returning. Over time, your muscles will adapt to healthier alignment, making good posture feel like second nature rather than a forced effort.

Reversing Posture Pain Through Body Awareness

A key component of reversal is learning body awareness, sometimes called proprioception. This is your ability to recognize and control your body’s position in space. Physical therapists often train patients to notice when they are slouching or tilting the pelvis forward.

Over time, this awareness becomes automatic, allowing you to adjust before strain develops. Simple cues, such as keeping your ears in line with your shoulders, can make a significant difference in long-term comfort.

Strength and Mobility for Faster Recovery

Additionally, integrating strength and mobility into your daily life, not just during workouts, can speed up posture recovery. This might involve doing a set of wall angels during a coffee break or standing on one leg while brushing your teeth to improve balance. Small, repeated actions train your muscles to hold you in optimal alignment without conscious effort, reducing the likelihood of recurring pain.

Conclusion

Poor posture is not just a cosmetic concern, it has far-reaching effects on your physical and mental well-being. From neck and shoulder pain to lower back strain, hip tightness, and even headaches, poor posture can trigger a cascade of discomfort throughout the body. Understanding these pain areas and how they interconnect is crucial for preventing long-term damage.

By taking proactive steps, such as incorporating regular movement, strengthening exercises, and mindful alignment, you can break the cycle of pain and set the foundation for a healthier, more balanced body. Good posture is an investment in your overall health, offering benefits that extend beyond the physical to improve your mood, energy, and overall quality of life.

Chronic pain is a complex and often frustrating experience, and finding a safe medication to manage it long-term is one of the biggest challenges patients and doctors face. It’s not always about completely eliminating the pain, it’s about making it manageable enough so that daily life can continue with some sense of normalcy. For people living with conditions like osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia, nerve pain, or recurring migraines, the idea of taking medication for years, or even decades, is daunting. The risks, side effects, and effectiveness of each option must be weighed carefully, especially when safety is the priority.

So, the question that often arises is what the safest pain medication for long-term use truly is. There’s no one-size-fits-all answer, but understanding your options can make the decision more informed and personal. What is the safest pain medication for long-term use? Let's find out.

Acetaminophen

Acetaminophen (Tylenol) is often the first suggestion when managing chronic pain, especially for joint or muscle aches.

Acetaminophen is considered one of the safest over-the-counter pain relievers when used at recommended doses, but it has limitations and hidden risks. It works well for mild to moderate pain and doesn’t irritate the stomach like some NSAIDs. People with gastritis or peptic ulcers often prefer it for that reason.

However, it has no anti-inflammatory effect, so for those dealing with inflammation-related conditions, it may not provide full relief. Also, while it’s gentle on the stomach, it can be hard on the liver. Long-term use or high doses, especially when combined with alcohol, increase the risk of liver damage. The FDA recommends not exceeding 4,000 mg per day, but many doctors suggest staying closer to 3,000 mg to be on the safe side.

For individuals with liver issues or those who regularly drink alcohol, acetaminophen may not be the best long-term solution, even though it's generally viewed as safe in the general population.

NSAIDs

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen (Advil), naproxen (Aleve), and prescription versions such as meloxicam or diclofenac are widely used for chronic pain, especially pain related to inflammation.

While NSAIDs are effective in reducing both pain and inflammation, their long-term use can come with serious side effects involving the stomach, kidneys, and heart. For people with arthritis or musculoskeletal pain, NSAIDs are often more effective than acetaminophen because they address swelling and joint stiffness.

However, chronic NSAID use raises the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, ulcers, and kidney damage. Seniors and those with high blood pressure or pre-existing kidney conditions are especially vulnerable. There's also an increased risk of cardiovascular events like heart attack or stroke, particularly with long-term use of certain NSAIDs.

To reduce risks, doctors often recommend the lowest effective dose for the shortest duration possible. In some cases, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are prescribed alongside NSAIDs to protect the stomach lining.

Still, this class of drugs is a mixed bag. They may be tolerated well by some people for years without complications, while others may develop problems within weeks or months.

Topical Pain Relievers

Not all pain medications are taken orally. In fact, some of the safest pain treatments for long-term use are applied directly to the skin.

Topical medications like diclofenac gel, lidocaine patches, and capsaicin cream offer localized relief without exposing the whole body to systemic side effects. This makes them an appealing option for people with chronic pain in specific joints or areas, such as knees, shoulders, or lower back.

Diclofenac gel, for example, is an NSAID but applied topically, which significantly reduces the risk of stomach issues and kidney problems. It’s commonly prescribed for osteoarthritis. Lidocaine patches numb the area temporarily and are useful for nerve pain, especially post-shingles or diabetic neuropathy. Capsaicin cream, made from chili peppers, gradually reduces pain signal transmission when used regularly.

While these aren’t ideal for deep, widespread pain, they are generally safe and can be used alongside oral medications for a more comprehensive plan.

Antidepressants and Anticonvulsants for Nerve Pain

Chronic pain isn’t always caused by tissue damage. Nerve-related pain, or neuropathic pain, requires a different approach altogether.

Medications originally developed for depression or seizures are now frontline treatments for chronic nerve pain, and many are considered safe for long-term use when monitored. These include drugs like amitriptyline, nortriptyline, duloxetine (Cymbalta), and gabapentin or pregabalin (Lyrica).

Duloxetine is FDA-approved for conditions like fibromyalgia and chronic musculoskeletal pain. Gabapentin and pregabalin are widely prescribed for diabetic nerve pain, sciatica, and other nerve conditions. These medications don’t carry the same liver or kidney risks as NSAIDs, but they do come with their own considerations.

Fatigue, dizziness, and mood changes are common early side effects, and some people may experience weight gain or brain fog. For those with mental health concerns, these drugs may actually help improve mood and sleep, making them a two-in-one treatment. However, for others, side effects can outweigh the benefits.

These medications typically require careful dose titration and ongoing check-ins, but for many, they offer long-term relief with relatively low physical risk.

Opioids

For severe chronic pain, such as that caused by cancer, serious injury, or multiple failed surgeries, opioids may be part of the conversation. But long-term use brings many red flags.

While opioids are powerful pain relievers, they carry the highest risk of dependence, tolerance, and overdose, making them a last resort for long-term pain treatment. Drugs like oxycodone, hydrocodone, morphine, and fentanyl can provide much-needed relief in situations where other medications fail, but their long-term safety profile is deeply problematic.

Even at stable doses, opioids can cause constipation, hormone imbalance, depression, and increased sensitivity to pain over time (a condition called opioid-induced hyperalgesia). Tolerance often means that people need higher and higher doses to achieve the same effect, which increases overdose risk.

Some patients, under careful pain management programs, may use opioids safely for years. These are often cancer patients or individuals in hospice care. For others, especially younger individuals with non-terminal conditions, the risks usually outweigh the rewards.

In recent years, the medical community has become more cautious about prescribing opioids, and they are rarely recommended as a first or even second-line treatment for chronic pain.

Medical Cannabis and CBD

With growing legalization, more people are turning to cannabis-based products for pain relief.

CBD and medical cannabis offer an alternative for some chronic pain sufferers, but long-term safety data is still emerging. Cannabidiol (CBD), a non-psychoactive component of cannabis, has shown promise for treating inflammation, nerve pain, and even arthritis discomfort.

Unlike opioids, CBD does not cause dependence and is generally well-tolerated. Side effects are usually mild and may include drowsiness, diarrhea, or changes in appetite. Medical marijuana (THC-containing products) is stronger but can impair memory, coordination, and motivation over time. It may also carry a risk of dependency with frequent use.

For people seeking alternatives to prescription drugs, cannabis-based therapies are worth exploring with a doctor’s guidance. However, legal access, standardization, and cost remain challenges across many states.

Non-Drug Approaches That Support Long-Term Relief

Sometimes, the safest “medication” isn’t medication at all. For long-term pain sufferers, combining pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical methods often delivers the most sustainable results.

Exercise, physical therapy, mindfulness, and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) are all evidence-based tools that can reduce pain perception and improve quality of life without the side effects of drugs. In fact, the CDC recommends non-drug approaches as first-line treatments for many types of chronic pain.

Low-impact exercises like walking, swimming, and yoga build strength and flexibility, reducing strain on painful joints. CBT helps patients reframe how they experience pain and build coping skills. Mindfulness and meditation can lower stress, which directly influences pain intensity.

Integrating these methods doesn't mean you have to quit medications altogether. But when used together, they may reduce the need for higher drug doses and lower the risk of long-term complications.

Which Pain Medications Are Safe for Specific Conditions?

Different pain conditions call for different treatments, and safety varies based on what you're dealing with. Here's a general overview:

| Condition | Generally Safer Long-Term Options | Caution/High-Risk Options |

| Osteoarthritis | Acetaminophen, topical NSAIDs, duloxetine | Oral NSAIDs, opioids |

| Neuropathy (Nerve Pain) | Gabapentin, pregabalin, amitriptyline | Opioids, long-term NSAIDs |

| Chronic Back Pain | Physical therapy, NSAIDs (short-term), duloxetine | Opioids, muscle relaxants |

| Fibromyalgia | Duloxetine, milnacipran, low-dose amitriptyline | Opioids, high-dose NSAIDs |

| Migraines | Topiramate, propranolol, tricyclics | Daily NSAID use, opioids |

| Cancer Pain | Opioids under supervision | High-dose NSAIDs (due to organ damage) |

This table is a helpful guide, but it's not a substitute for individual evaluation by a healthcare provider. The safest option for one person might not be safe for another, depending on age, medical history, and other medications.

So, What Is the Safest Pain Medication for Long-Term Use?

Ultimately, the safest pain medication for long-term use depends on the cause of your pain, your overall health, and how your body responds to different treatments.

For most people, medications like acetaminophen, certain antidepressants, topical NSAIDs, and low-dose nerve pain drugs offer the best balance between safety and effectiveness. But there’s no universal winner. It's about finding a regimen that works for your body without compromising your health over time.

This is why pain management often involves trial and error, regular follow-up, and a multidisciplinary approach. The goal isn’t just to dull the pain, but to maintain function, improve mood, and preserve quality of life.

Conclusion

Pain that lingers for months or years changes everything, from how you sleep and move to how you think and feel. That’s why choosing the right long-term pain management plan is a decision that should involve both personal reflection and professional guidance.

While some medications are more tolerated over time than others, there is no magic pill. The safest approach to long-term pain relief is often a thoughtful combination of low-risk medications, non-drug therapies, and regular check-ins with your healthcare team. Whether you're managing arthritis, nerve pain, or something more complex, safety should never take a back seat to quick fixes.

Understanding your body’s needs and staying open to adjustments along the way is the real key to sustainable relief.

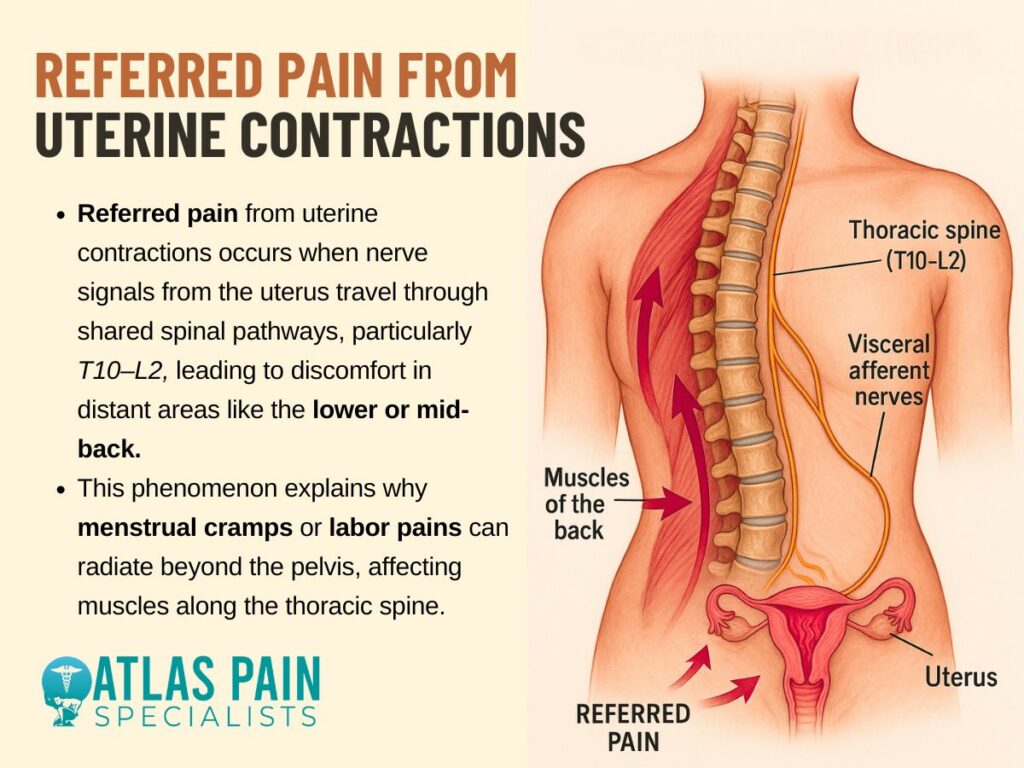

Upper back pain during your period is often caused by hormonal fluctuations, muscle tension, and poor posture related to menstrual symptoms. Menstruation is a complex biological process that can bring a wide range of physical and emotional effects including cramps, fatigue, mood swings, and sometimes surprising discomfort in the upper back. While lower abdominal and lower back pain are well-known period symptoms, upper back pain can be more unexpected and confusing.

If you’ve ever wondered, “Why does my upper back hurt on my period?” you’re not alone. This article explores the hormonal, muscular, and postural factors that contribute to this pain and offers practical strategies to help you manage it more comfortably.

Understanding Menstrual Pain

Understanding how hormones affect your body during menstruation can help explain many of the physical symptoms you experience, including pain. Hormonal fluctuations throughout your cycle play a key role in triggering and intensifying menstrual discomfort.

1. The Role of Hormones

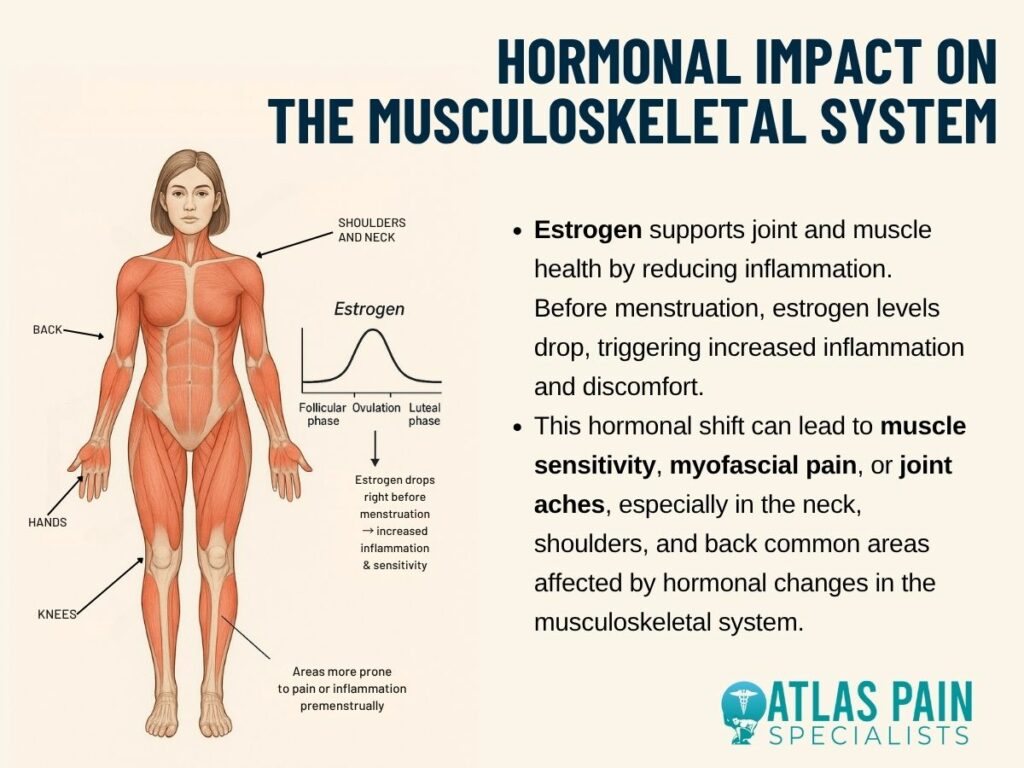

Hormones like estrogen and progesterone regulate the menstrual cycle and fluctuate significantly before and during your period. A drop in these hormones, especially estrogen, can increase your sensitivity to pain and contribute to inflammation and muscle tension.

2. Prostaglandins and Cramping

Prostaglandins are hormone-like substances released by the uterus to help shed its lining. High levels of prostaglandins can cause stronger uterine contractions, which not only lead to cramps but can also radiate discomfort to the lower and upper back.

3. Impact on Mood and Stress

Hormonal shifts can also influence mood, increasing feelings of anxiety or irritability. Elevated stress levels often lead to muscle tightness, especially in the shoulders and upper back, adding to physical discomfort.

By understanding the hormonal processes behind your menstrual cycle, you can better recognize the causes of pain and find targeted ways to manage it more effectively.

Common Causes of Upper Back Pain During Menstruation

Upper back pain during menstruation may not be as widely discussed as lower back or abdominal cramps, but it's a fairly common and often overlooked symptom. Understanding the possible causes can help you manage this discomfort more effectively each cycle.

1. Referred Pain from Uterine Contractions

Though the uterus is located in the lower abdomen, the nerves and muscles it affects can create a domino effect throughout the torso. This phenomenon, known as referred pain, means that pain originating in one area is felt in another. Severe uterine cramping may irritate nerves connected to muscles in the mid-to-upper back, especially around the thoracic spine.

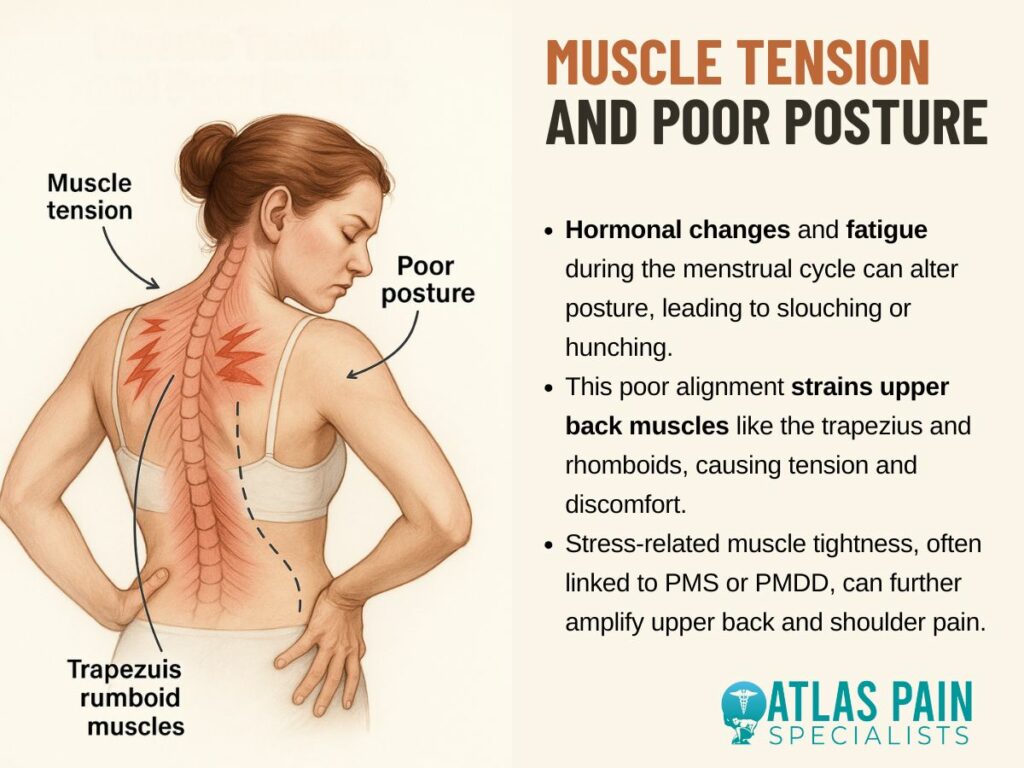

2. Muscle Tension and Poor Posture

Hormonal changes can cause bloating, breast tenderness, and fatigue, which may subconsciously alter your posture. Slouching or hunching over—particularly when lying in bed or using a heating pad—can strain the trapezius and rhomboid muscles, leading to upper back pain.

Muscle tension is also more likely when you’re stressed, and many people experience heightened anxiety or irritability during their menstrual cycle due to premenstrual syndrome (PMS) or premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD).

3. Hormonal Impact on the Musculoskeletal System

Estrogen has anti-inflammatory properties and helps maintain muscle and joint health. As estrogen levels fall right before your period, inflammation may rise and muscle pain may become more noticeable. Some women experience myofascial pain or joint sensitivity, particularly in the back, shoulders, and neck.

4. Breast Swelling and Upper Thoracic Strain

Hormonal fluctuations can lead to breast engorgement or tenderness before and during your period. Increased breast size or weight can pull the upper back and shoulder muscles forward, placing extra strain on the thoracic spine and scapular region.

5. Underlying Conditions Exacerbated by Menstruation

Conditions like endometriosis, fibromyalgia, or chronic back disorders can worsen with hormonal shifts. Endometrial tissue may implant near the diaphragm or spine, which could refer pain to the upper back during menstruation.

Similarly, fibromyalgia sufferers often experience intensified musculoskeletal pain during their cycle.

6. Stress and Anxiety

The menstrual period can be a time of increased emotional sensitivity, stress, and anxiety for many. Psychological stress can manifest physically as increased muscle tension, particularly in the neck, shoulders, and upper back.

The body's "fight or flight" response, when activated by stress, can lead to chronic muscle clenching and pain.

While upper back pain during menstruation can be frustrating, it’s often a result of natural hormonal and physical changes. Identifying the cause is the first step toward finding effective relief and improving comfort during your cycle.

Other Contributing Factors

In addition to hormonal shifts and uterine activity, several other factors can contribute to upper back pain during menstruation. Recognizing these additional influences can help you address the pain more holistically.

1. Dehydration

Not drinking enough water, which can happen during your period, can lead to muscle cramps and worsen existing aches. Proper hydration is vital for muscle function and comfort.

2. Dietary Factors

Eating foods high in sugar, processed ingredients, or unhealthy fats can increase inflammation throughout your body. These dietary choices might intensify muscle aches, including those in your upper back, during your period.

3. Sleep Disturbances

Pain, discomfort, or hormonal shifts can disrupt sleep during menstruation. Poor sleep quality prevents your body from recovering, making muscle aches more noticeable and increasing your sensitivity to pain.

4. Underlying Medical Conditions

Pre-existing conditions like scoliosis, fibromyalgia, or even endometriosis can see their symptoms worsen during menstruation, leading to more pronounced upper back pain. Rarely, digestive issues like IBS or gallstones might also cause referred pain in the upper back.

Being aware of these contributing factors can help you take a more comprehensive approach to managing upper back pain. With a combination of lifestyle adjustments and targeted care, you can reduce discomfort and improve your overall well-being during your period.

When to Seek Medical Attention

While upper back pain during menstruation is often manageable with lifestyle changes and self-care, there are times when it could indicate something more serious. Knowing when to consult a healthcare provider is important for your overall health and peace of mind.

1. Persistent or Severe Pain

If your upper back pain is intense, lasts beyond your period, or interferes with daily activities, it could signal an underlying issue. Chronic or worsening pain should always be evaluated by a healthcare professional.

2. Accompanying Unusual Symptoms:

If your back pain is accompanied by symptoms like fever, numbness, chest pain, or difficulty breathing, it may be unrelated to menstruation and require immediate medical attention. These signs could point to conditions like infections or nerve problems.

3, No Relief from Over-the-Counter Treatments

When common remedies like heat, stretching, or pain relievers fail to provide relief, it might be time to seek medical advice. Ineffectiveness of standard treatments can suggest a need for further investigation.

Being aware of these warning signs ensures you don't overlook potentially serious health concerns. If something feels unusual or unmanageable, it’s always best to consult a healthcare provider for proper evaluation and guidance.

Coping Strategies and Remedies

Managing upper back pain during your period involves both immediate relief techniques and long-term lifestyle adjustments. Incorporating a few simple habits can help ease discomfort and improve your overall menstrual experience.

1. Heat Therapy

Applying a heating pad or warm compress to your upper back can relax tight muscles and increase blood flow. This soothing method often provides quick relief from tension and soreness.

2. Stretching and Gentle Exercise

Light activities like yoga, walking, or targeted stretching can reduce stiffness and improve posture. Movement also helps release endorphins, which act as natural painkillers.

3. Over-the-Counter Pain Relief

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen, can reduce inflammation and alleviate both menstrual cramps and back pain. Be sure to follow dosage instructions or consult a healthcare provider.

4. Posture Awareness

Maintaining good posture, especially when sitting for long periods, can prevent added strain on the upper back. Using ergonomic chairs or lumbar supports may also be helpful.

5. Stress Reduction Techniques

Practices like deep breathing, meditation, or massage can help reduce emotional tension that often contributes to physical pain. Managing stress levels can minimize muscle tightness in the shoulders and back.

Using a combination of these strategies can make a noticeable difference in your comfort during menstruation. By listening to your body and adopting supportive habits, you can reduce pain and feel more in control of your cycle.

Managing Upper Back Pain During Your Period

Managing upper back pain during your period involves a mix of practical self-care techniques and mindful lifestyle choices. By addressing both the physical and emotional aspects of pain, you can significantly reduce discomfort and improve your overall well-being.

1. Maintain Regular Exercise

Engaging in consistent, moderate exercise helps strengthen back muscles and improve circulation, which can reduce menstrual-related pain. Activities like swimming, walking, or yoga are particularly beneficial for easing muscle tension.

2. Stay Hydrated and Eat Well

Proper hydration and a balanced diet rich in anti-inflammatory foods can help minimize bloating and muscle cramps. Avoiding excessive caffeine and salty foods may also reduce discomfort.

3. Prioritize Rest and Sleep

Getting enough quality sleep supports your body’s healing processes and reduces stress, which can exacerbate pain. Establishing a calming bedtime routine can improve sleep during your period.

4. Use Supportive Pillows and Ergonomics

Sleeping with pillows that support your back and maintaining good posture at work or home can lessen strain on your upper back. Ergonomic adjustments help maintain spinal alignment and prevent muscle fatigue.

By combining these management techniques, you can create a personalized approach to ease upper back pain during your menstrual cycle. Consistency and self-awareness are key to finding relief and enhancing your comfort each month.

Navigating Period-Related Upper Back Pain: A Summary

Upper back pain during your period is a common but often misunderstood symptom influenced by a combination of hormonal changes, uterine activity, muscle tension, and emotional factors. While it may feel confusing or unexpected compared to typical menstrual cramps, recognizing the root causes can help you manage the discomfort more effectively.

Simple lifestyle adjustments, stress management, and self-care techniques can make a significant difference in easing this pain. Being aware of why upper back pain occurs during menstruation allows you to take control of your symptoms and improve your menstrual health.

If the pain is severe or persistent, seeking medical advice is important to rule out other issues. With the right approach, managing this pain can become easier each cycle.

A lot of people think their biceps are causing trouble when there is a deep, nagging ache in their upper arm. However, the problem might be the muscle just beneath it.

That is the brachialis, and it's used every time you pick up a grocery bag, carry your backpack, or even bend your elbow to sip your coffee when something throws it off balance like too much movement, bad form during a workout, or simply pushing through fatigue it can start to ache.

The thing with this kind of pain is it often starts slowly. One day, you're fine, and the next, a basic task like brushing your hair or pulling open a door feels uncomfortable.

The Brachialis Muscle

You may have heard of the biceps and maybe triceps when it comes to arm strength, but there’s another muscle in play. The brachialis sits deep in the front part of your upper arm.

It runs from the lower half of your upper arm bone, known as the humerus, and attaches to the top of the ulna, which is one of the bones in your forearm. This positioning connects the upper and lower parts of your arm in a very direct way.

The muscle doesn’t show much on the surface, but its structure allows it to do most of the work when you bend your elbow. It can generate a lot of force when pulling the forearm toward the shoulder.

Why the Brachialis Starts to Hurt

The brachialis is built in a way that allows it to act without depending on wrist rotation, which makes it essential in movements that involve raw pulling strength. Because it doesn’t factor in the position of your palm, it is still in use whether your hand faces up, down, or sideways.

That makes it active during more movements than you might expect. Over time, all this repeated effort adds up, especially if the muscle isn’t given enough rest or support from surrounding muscles.

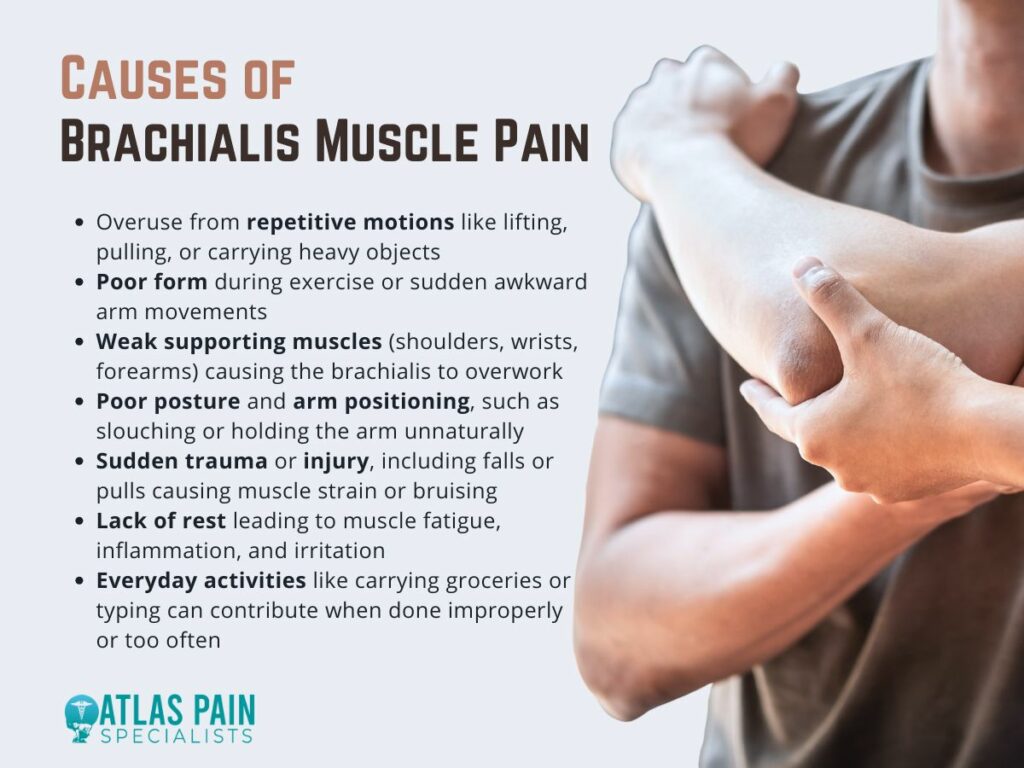

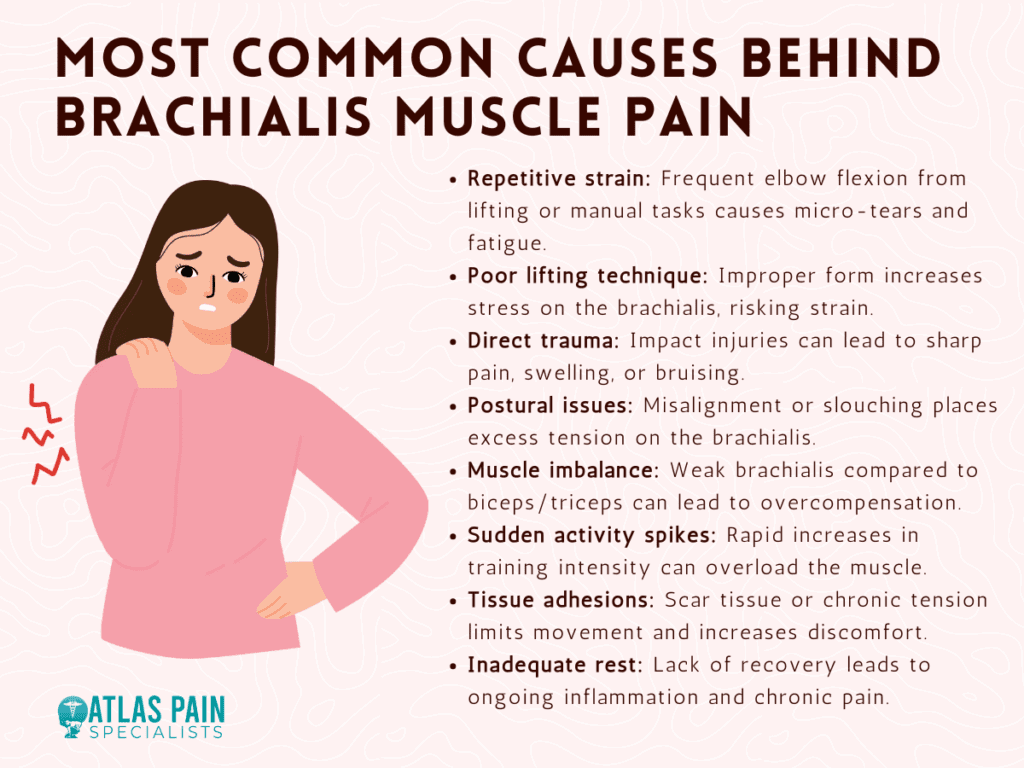

- Repeating the Same Movements Too Often

Doing the same motion over and over can wear the brachialis down. You might be lifting weights, pulling heavy objects, or even working a job that requires a lot from your arms.

These repeated motions can make the muscle tired and inflamed. Even something as routine as carrying groceries or typing at a poorly positioned desk can slowly put pressure on it.

When you don’t give your arm enough time to recover, the brachialis starts to resist. It can tighten up, become sore, or feel irritated during basic movements.

- Lifting Too Much or Moving the Wrong Way

Trying to push past your limits with weights or heavy objects can overload the muscles. The brachialis is used during pulling and curling motions, so lifting without proper form can cause it to strain.

You might not feel the pain right away, but soreness can show up hours later and stick around longer than expected. Moving the wrong way, twisting your arm awkwardly, or yanking something without preparation can also cause sudden stress.

These quick, careless motions are often the start of a sharp, constant pain that won’t go away on its own.

- Weak Supporting Muscles Around the Arm

When nearby muscles don’t do their part, the brachialis ends up doing too much. Weak shoulders, tight forearms, or unstable wrists can force it to overcompensate.

This extra effort wears it out faster and makes it more likely to become irritated. Without balance in the arm, even small tasks can feel harder on this one muscle.

Improving strength in the rest of your upper body can take pressure off the brachialis and help it work without stress.

- Poor Posture and Arm Positioning

Your posture affects your arms more than you’d expect. Slouching, hunching over a desk, or holding your phone at an awkward angle for long periods can lead to poor arm alignment.

That kind of positioning can stretch or compress the brachialis in unnatural ways. Even small changes in how you sit, work, or carry things can make a difference.

Keeping your arm in a more natural position allows the muscle to move freely, which helps reduce unnecessary tension over time.

- Sudden Injury or Trauma

A fall, collision, or even a bad pull can shock the muscle. These moments might seem minor at first, but the brachialis can bruise, tear slightly, or become inflamed from one wrong move.

Pain from this kind of injury usually comes on quickly and feels sharper or deeper than soreness from overuse. Letting the muscle heal fully before going back to normal activity can help avoid making things worse.

Rushing back into movement without care can turn a minor issue into a longer recovery.

What Brachialis Pain Feels Like

Pain in your arm sometimes feels vague, or overlaps with other muscles, making it tough to pinpoint exactly where it's coming from. When the brachialis is involved, the discomfort often feels deep and tucked under the surface, almost like something is pulling inside your arm rather than on top of it.

You may notice it most when your arm is in motion, especially when you bend the elbow or carry something heavy.

- A Deep Ache That Doesn’t Quite Feel Like the Biceps

Brachialis pain tends to sit low in the upper arm, close to the elbow, and not directly in the center like typical biceps soreness. It can feel like a tight or aching sensation that rests just beneath the biceps, making it harder to identify right away.

You might notice it during elbow flexion or when picking up items, even if they aren’t that heavy. Because this muscle isn’t on the surface, the pain often feels buried.

It may seem like it comes from the joint or even the bone, but it’s actually the brachialis.

- Sharp Discomfort With Simple Elbow Movements

You might feel a sharper kind of pain when you bend your elbow under pressure. Lifting weights, pulling something toward you, or even opening a tight jar can trigger it.

This sharpness usually fades with rest but returns during the next effort. It’s the kind of sensation that makes you hesitate mid-movement, not because the object is too heavy, but because the muscle sends a quick warning.

This warning can become more regular and harder to ignore.

- Soreness or Tenderness When You Press the Area

Running your fingers along the inside of your upper arm, especially near the elbow, might reveal a spot that feels unusually tender. It’s not the same as general arm soreness.

The tenderness is often focused and can be uncomfortable even with light pressure. This spot can feel like a bruise or a knot, depending on how much the muscle has been overworked or strained.

Pressing it may even recreate the pain you feel during movement, which helps confirm that the brachialis is likely involved.

- Weakness and Tightness That Comes Out of Nowhere

When carrying stuff or doing curls at the gym your arm might feel weaker than usual. That sense of weakness isn’t always pronounced, but it can be frustrating.

It feels like your arm just doesn’t want to work as hard as it used to. Along with that weakness, there might be a tight sensation that limits how far you can extend or bend your elbow.

It may feel like your range of motion shrunk slightly without a clear reason. These signs often appear together, especially in the early stages of brachialis strain.

When to Seek Help

Not all muscle pain needs medical attention. Most of the time, a little rest, a warm compress, or some light stretching can settle things down.

But there are moments when pain isn’t just a passing issue. It keeps coming back, grows worse, or starts to affect how you live your day. That’s when you should stop guessing and consider getting help.

- When Rest Doesn’t Seem to Help

Taking a break should usually ease a sore muscle, especially if overuse or a minor strain causes discomfort. But if you’ve given your arm time off, avoided heavy lifting, and skipped workouts, yet the pain still lingers, it may point to something deeper.

A muscle that doesn’t respond to rest may be dealing with a more serious strain or a small tear. Pain that sticks around longer than a week or feels just as sharp every time you return to movement could be a sign that recovery isn’t happening as it should.

A trained specialist can help figure out what’s actually going on.

- When the Pain Gets Worse Over Time

What starts as a light ache shouldn’t gradually turn into stabbing pain. If things feel more painful after just a few days, even without much activity, that’s not something to ignore.

Muscles that get worse instead of better are usually irritated beyond the point of simple soreness. Increased pain during basic movements like brushing your teeth or pouring a drink is a sign that the muscle isn’t healing on its own.

The longer it’s left untreated, the more inflamed or damaged it can become.

- When You Notice Swelling, Numbness, or Bruising

Swelling or a visible change in the shape of your arm may suggest more than a basic strain. The brachialis doesn't usually swell unless a significant pull or tear is experienced.